Hello! My name is Federico, and I am a student of political science in Italy. For SUSWA, I am currently completing an internship, having started in February 2024.

Two years ago, I worked on a GEDSI (Gender Equality, Disability and Social Inclusion) data analysis, examining the extent and types of restrictions that affect women during their menstrual cycle in some Nepali communities.

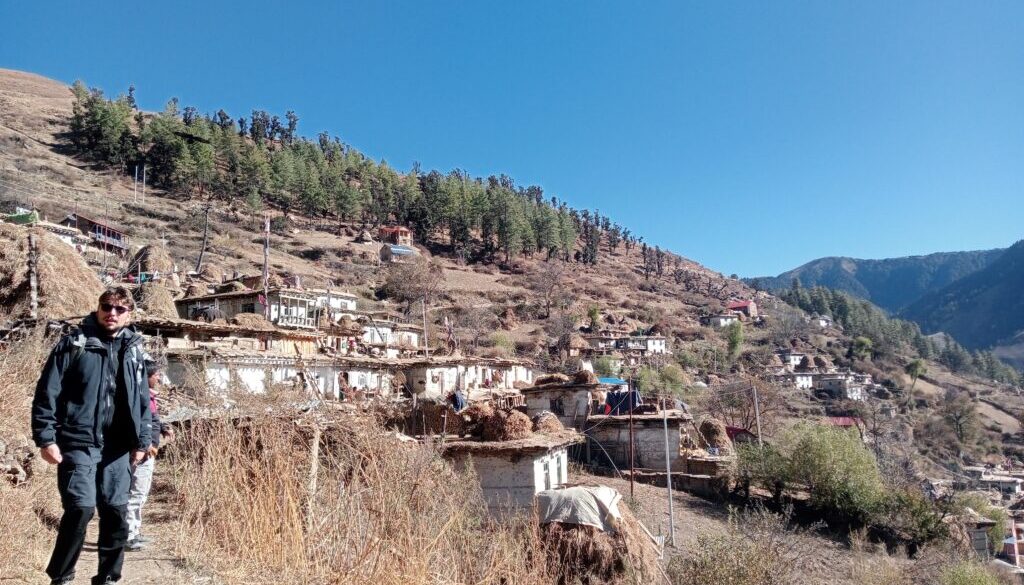

In November 2025, I conducted a field visit to Sinja Rural Municipality and Hima Rural Municipality, Jumla, with Rita Khadka, SUSWA’s GEDSI Compliance Monitoring Officer. The purpose of the visit was to carry out a GEDSI Audit to assess the situation within these palikas.

We visited the Sinja local government office, the WASH Unit, and the communities involved in SUSWA’s intervention to observe conditions related to gender equality, disability, and social inclusion (GEDSI), and to sanitation and hygiene. Rita’s role was to conduct the interviews and cross-verify the documents and reports to ensure that GEDSI principles were properly integrated, while my focus was to reflect on the working methodology and collect data connected to the work I carried out two years ago, assessing the current conditions within these communities.

During the visits, I heard various stories about the discrimination that women experience in their daily lives, such as not entering places like the kitchen, not touching or consuming dairy products, not using taps, or not entering temples. I also had the opportunity to visit two different animal sheds where women from these communities spend the night during their menstrual period. One of them—a cowshed the cattle had left only moments earlier—made a particularly strong impression on me.

The shed consisted of three small rooms: in the first one, the light was already dim, and the farther we went inside, the more it disappeared, until we found ourselves in complete darkness. In the last room, there was only hay on the floor; I felt as if I were inside a cave, and the smell hit me immediately—an overwhelming mix of animal feed (rotting apples) and cow dung.

When we stepped back outside, the sunlight felt blinding, and even the air we breathed seemed entirely different compared to just a few seconds before. A woman explained that during the day, she and the other female members of the household don’t perform their usual tasks; instead, they must go into the forest to collect firewood, mainly to stay as far away from home as possible.

When we returned to the meeting, the women in the community pointed out—half surprised and half amused—that while we were in the shed, I had stepped on a pile of cow dung. Of course, I wasn’t concerned about my shoe; what truly struck me was how these women seemed more worried about my dirty shoe than about the unfair treatment they themselves had to endure.

The photo on the left refers to the second animal shed I visited (the one I described earlier was too dark to photograph), while the photo on the right shows a tap that, because of the image of God on it, could not be used by women during their menstrual period. Before the construction of a new SUSWA tap, they had to go to the river to meet their everyday needs.

It has been deeply interesting and truly eye-opening to witness firsthand the reality in which so many women are living. These experiences allowed me not only to understand their daily challenges on a more human level but also to reflect on the importance of continuing to work toward dignity, equality, and inclusion. Although I had engaged with these issues two years earlier—albeit only from the data side—the reality I encountered in the village was vastly different from anything I had experienced in Europe, and it deeply moved me. Even though I understood the cultural reasons behind certain practices, one question kept coming to mind: cows and goats give birth, bleed, and are cared for every day without being sent away—so why should women have to sleep apart during their own cycle?

Federico Crippa